Real-world Android Malware Analysis 1: eblagh.apk

by purpl3f0x

Intro

Over the last few months I have been cultivating a new skill that I’m getting to use at work: Android malware reverse engineering and analysis. There is still a lot to learn, so I’m starting to look for more opportunities to practice. Fortunately, there are a couple of malware hunting accounts on Twitter who can feed me a steady flow of suspicious APKs to break down. For this write-up I’ll be analyzing a sample of suspected malware that is not on the Play Store.

Static Analysis with Open-Source Tools

Finding a lead

I started out by checking @malwrhunterteam on Twitter to see if they had recently pointed out any malicious APKs that I could analyze. Luckily for me, they posted a fresh lead about an hour before I got off work.

A little bit of OSINT

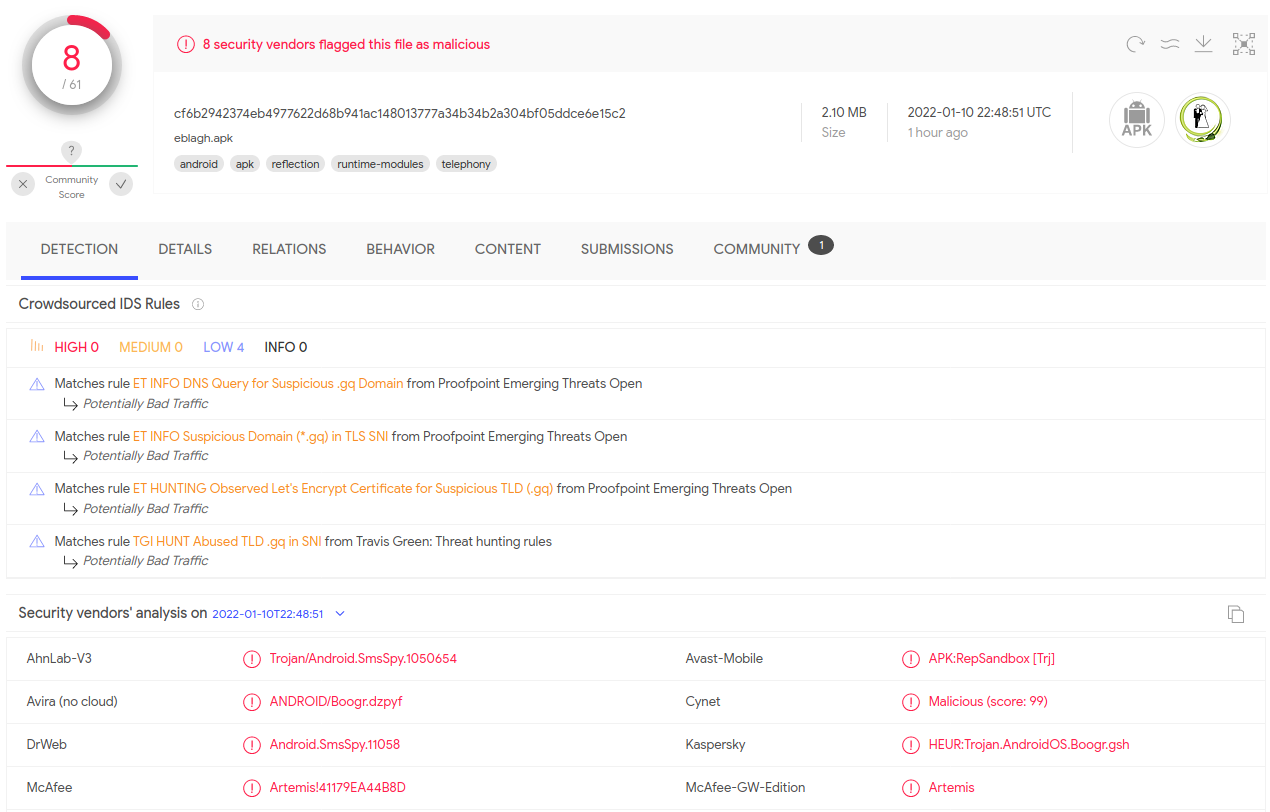

I always like to do a bit of OSINT before I start digging into the code, to try to get an idea of what I’m getting into. A good starting place is taking the digest in the Tweet above and searching it in VirusTotal:

It seems like some of the detections are coming back with SmsSpy, which leads me to initially believe that this could be spyware, so that is where I’ll direct my efforts starting out.

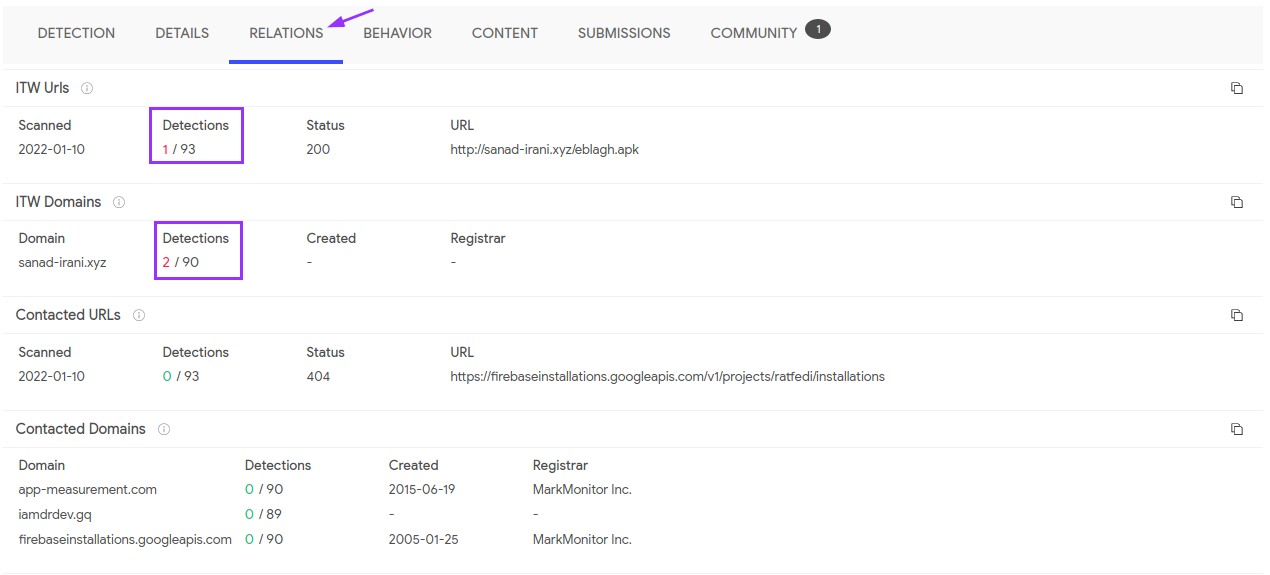

Next, I’ll look around more in VT to see what else turns up:

It seems that some of the domains contacted by the app are coming back as malicious. It may be due to the fact that the sanad-irani domain is where the APK comes from. Unfortunately, the site appears to be down, which was disappointing because that stopped me from getting the APK.

Fortunately, I remembered that if you have an account with VirusTotal, they allow you to download samples. Logging in, I got a copy of the APK, and started with the code analysis.

Code Analysis

The most important place to start an investigation is the AndroidManifest.xml file. This file is always packaged with APKs, and it is where permissions are declared, among other things. For this analysis, I am using Jadx, an open-source tool for decompiling Java code.

Going off my previous assumption that this is possibly spyware, I look for any SMS-related permissions:

To be fair, there are many potentially dangerous permissions found here, but I highlighted those related to SMS since I’m currently operating under the assumption that this is spyware. I am not sure what the advertised usage of this app is supposed to be, since the originating site is offline, but this combination of permissions is a big red flag.

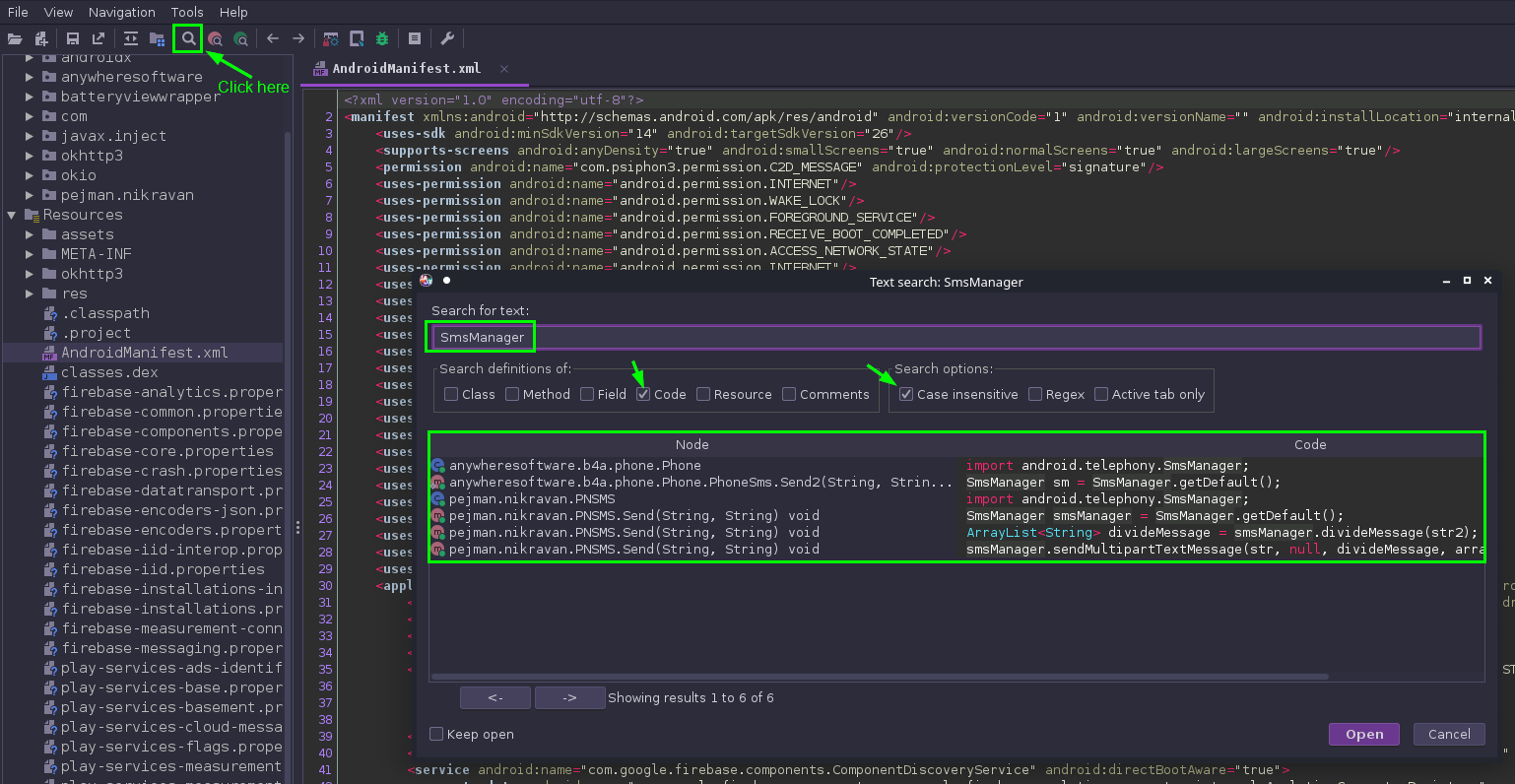

With this information in hand, I start looking for abuse of the SmsManager Android API:

We see here that there are a few classes that are calling the SmsManager API. We’ll have to drill into them one by one to see what’s really going on. This can be done by double-clicking one of the entries, and I started with the 2nd from the top entry:

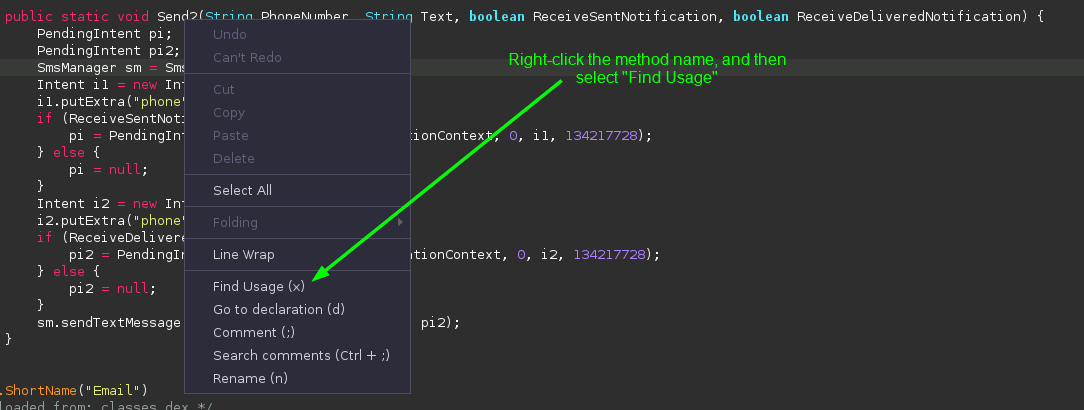

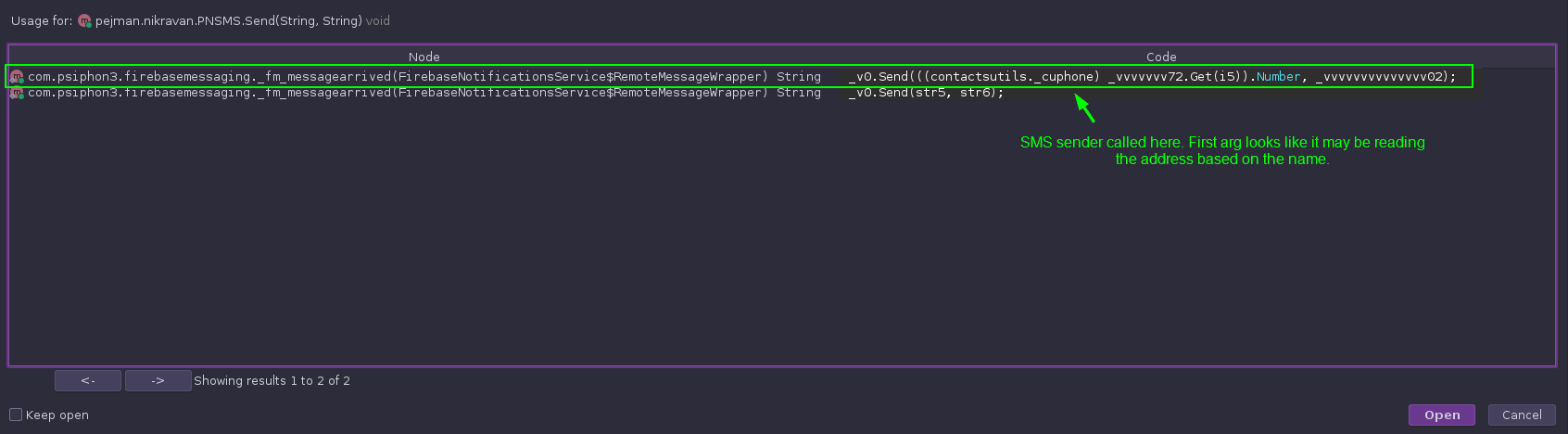

Not quite what I was expecting, but this is still suspicious. Most people probably don’t want an app sending text messages on their behalf. It’s not clear what’s being sent because the destination number and message body are stored in variables, which the method gets as arguments when it is called. So to start tracing what’s happening, we need to see what’s being passed to this code as it’s called. In Jadx, this can be done by right-clicking and selecting Find Usage to begin tracing the call chain:

The method is called by another method directly above it in the code. This method also gets the destination number and message body as arguments, so to learn more, we just keep back-tracing:

The Send method does not appear to be called. This is known as “dead code”, code that is defined but never called, so it never executes. This is a dead end, so we go back to searching for instances of smsManager and look at other classes using it:

It appears that we found another method for sending text messages, but the code is a bit beefier. Towards the bottom of the snip, we see where the SmsManager API is being invoked. To see where the actual SMS is sent, we scroll down:

Here we find a call to an API for sending multi-part text messages. To understand the arguments being passed to it, we can look up the API on the Android developer web site:

Referencing this, we learn that the first argument is the destination number, the second argument is the source number, the third is the message body, and the fourth and fifth arguments are the previously defined intents to verify that the message was sent and received.

Now we resume the back-tracing of calls to see where this code is invoked:

There is a lot going on in this code, so let’s break it down one thing at a time.

First of all, this code looks like the app is receiving commands from somewhere and taking various actions based on the received message. This makes the app a borderline backdoor trojan, allowing an outside user to have some degree of control of the device via a C2.

Secondly, we can see methods that, based on the command name, appear to be collecting and reading the user’s stored text messages, and contacts. If this is taking place with no in-app disclosure, this would be the smoking-gun evidence to positively identify the app as spyware. We’ll have to dig into that code a little more to confirm this.

Third, it appears that the SMS sending method gets phone numbers from the device’s address book. This activity could earn the app the designation of being spam, as it is covertly collecting the numbers of the victim’s friends and family and blasting text messages out to them. That makes three different categories of malware that this app could fall under.

We scroll up to find the name of the method with all of this potentially malicious code in it:

Now this is slick. To avoid directly betraying the URL of the C2 by hard-coding the address, the app is connecting to a Firebase instance to get the commands. Firebase is an offering from Google that aids in the development of Android apps. It is not entirely uncommon to see malicious apps leveraging Firebase as a way of covertly contacting C2 servers, as traffic to Firebase URLs usually does not light up detections on VirusTotal or other automated scanners. Based on the code flow, this is how the app receives commands.

Before I go into the rabbit hole of tracing the call chain more, I scrolled back down to the code for the “getContacts” command to confirm that the app is reading the victim’s contacts:

It appears that the code is attempting to leverage SQL queries to get contacts. I personally have not seen this method used before, so it’s difficult to fully describe what is occuring here, but the evidence found so far very strongly suggests that this is where the app gets the contact details from the device.

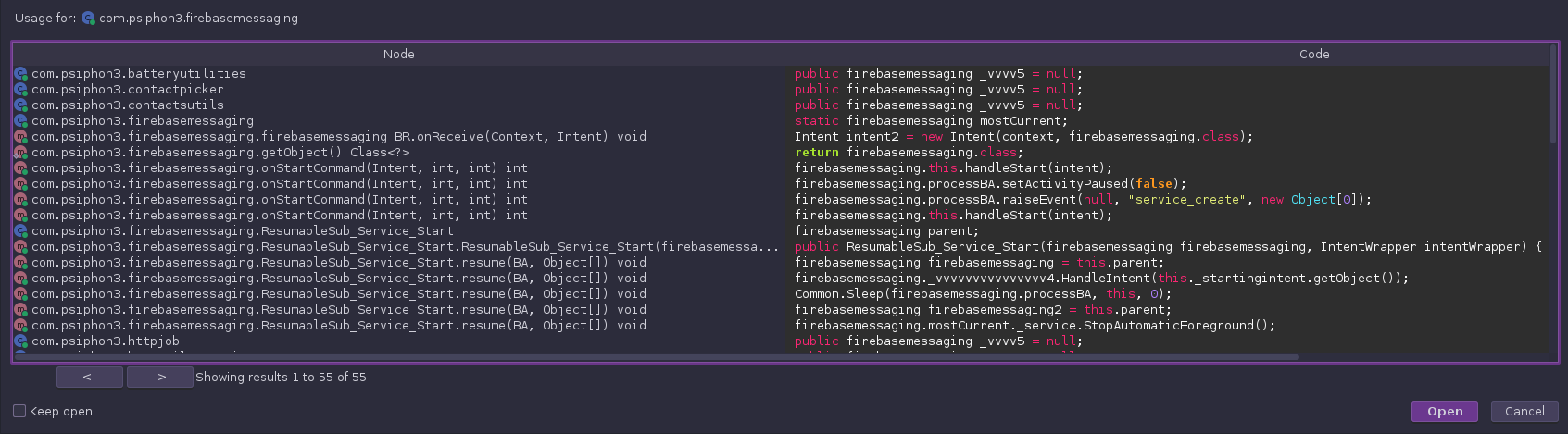

After this confirmation, I go back to back-tracing the call chain to the method that contained the malicious code:

It was disappointing enough for this to happen once before, but having it happen again is pretty deflating. There aren’t really any other leads for SmsManager to follow up on, so it’s looking like we hit a brick wall.

However, I tried looking for calls to the over class instead of just that method, and there seem to be many calls to it:

There are lots of calls here, and after checking a handful of them, there do not appear to be any strong leads to follow. At this point, I pivot to dynamic analysis.

Dynamic Analysis with Open-Source Tools

There are lots of Android Emulators out there, but I personally use Android Studio. It is primarily an IDE for creating Android apps, but it has an emulator bundled within it. Installing APKs is as simple as dragging-and-dropping the file onto the emulator.

Running the app on an emulator

Immediately upon launch, the app asks for a series of permissions that should make any user incredibly suspicious, and concerned:

After this, the dynamic analysis gets stone-walled:

It appears that the app is trying to use WebView to load a publicly hosted web page to continue. However, this web server appears to be down, so the app effectively does nothing at this point. There isn’t much more I can do for dynamic analysis.

Final verdict

Inconclusive. The code contains a lot of highly-suspicious activity, but most of it seems to be dead code, and dynamic analysis isn’t possible due to necessary public resources being offline.

Additionally, since I do not know the original intended purpose of the app, due to the originating website being down, it’s hard to conclusively say that the observed activity was malicious. However, due to the fact that most of the potentially malicious activity was triggered by C2 commands, and not user interaction, I’m leaning towards it being malware.

Overall, I would not trust this app in the slightest.

Conclusion

After getting my start in malware analysis by learning Windows malware, I am pleasantly surprised to find that Android malware analysis is much easier.

Instead of looking at x86/x64 Intel disassembly in debuggers and disassemblers, I have the advantage of reading decompiled Java code, which is much easier to read. Furthermore, the necessary AndroidManifest.xml file present in all Android apps gives some massive clues as to where analysis should begin.

Additionally, I personally feel that managing Android emulators is a bit faster and easier than spinning up Windows VMs for dynamic analysis.

All-in-all, I am thoroughly enjoying my new interest, and over the coming months I hope to become an experienced Android malware analyst.

References

Android API reference guide

Android Studio/Emulator

Jadx Java decompiler